WHEN COVENANT MEETS CAREGIVING

By Linda Waltersdorf Cobourn, EdD

I couldn’t go one more step.

Exhausted, I leaned against the wall, letting it hold me up. This had gone on far too long. People hurried past without noticing the weary woman with limp hair and a strained face.

I took a deep breath and prayed: God, give me strength. I need to do this. I need to keep my promise.

What I felt next wasn’t energy or resolve. It was something quieter but just as powerful—the steady assurance that if I kept putting one foot in front of the other, God would carry me through. He would honor the covenant I had made—not only with Him, but with my husband.

“The days are coming,” declares the LORD, “when I will make a new covenant with the people of Israel and with the people of Judah.”

— Jeremiah 31:31

A covenant is more than a promise. It is a sacred commitment—soul-deep and life-altering—that binds us to God. Throughout Scripture, we see God entering into covenant relationships with humanity: His promise to Noah never to flood the earth again, His pledge to Abraham to make his descendants a great nation, and His commandments to Moses and the people of Israel. Each covenant reveals God’s faithful, unfailing love.

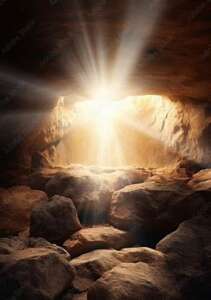

But the new covenant, prophesied in Jeremiah 31, is different. It’s not written on stone tablets, but on our hearts. It is sealed not by our works, but by Christ’s blood. As Pastor Amy shared during our Covenant Renewal Service, the Hebrew word for “covenant,” berith, implies a bond sealed by blood. In Abraham’s covenant, circumcision was the sign. In the New Covenant, Jesus is both the sign and the sacrifice.

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, recognized the importance of recommitment. In 1755, he led the first Covenant Renewal Service—a time of prayer, confession, and dedication to discipleship. Today, we are still called to lay our lives—our “service before the Lord as our acts and deeds.”

I’ve made two covenants in my life.

The first was when I was fourteen and accepted Jesus as my Savior. I’ve tried ever since to live as He would have me live—faithfully, though imperfectly.

The second was the marriage covenant I made with Ron. I promised before God to love and care for him “in sickness and in health.” That vow was tested again and again throughout Ron’s long illness. My body was often tired. My spirit sometimes faltered. There were moments when walking away seemed easier than continuing.

But every time I reached that point, God met me. On the way to hospital rooms—so many rooms, in so many hospitals—I would pray. And each time, He gave me just enough strength to make it one more day. Through nineteen years of caregiving, I kept my covenant with Ron the same way we keep our covenant with God: one faithful step at a time.

This is how we live out the New Covenant—not perfectly, but persistently. Not always with strength, but always with faith. We walk forward, even when it’s hard, trusting that God walks with us.

As our church family enters a season of transition—with Pastor Amy retiring to focus on her health, and Pastor Brandon coming to shepherd us—let’s remember where our true covenant lies. Our commitment is not to a single person, but to the God who called us together. We honor Pastor Amy’s legacy by continuing to walk in faith and service.

Let’s remain faithful—not just in words, but in daily, quiet acts of obedience.

Closing Prayer

Gracious God,

Thank You for being a covenant-keeping God. In every season, You remain faithful—even when we are weak or weary. Help us to live out our commitments with grace and perseverance. Strengthen us to keep walking, one step at a time, trusting in Your presence and power. As we enter this new chapter as a church family, bind us together in love and unity. May our lives reflect the promise of Your New Covenant—written on our hearts and sealed by the blood of Christ.

Amen.

Your turn, dear friends, How can you remain committed to your own covenant with God? How can you honor and carry on the work Amy has begun?